An interview with Professor Dana Fritz, Hixson-Lied Professor of Art (Photography) in the Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts. This post is part of our series, Brought to You by Tenure.

One thing that is often lost in the conversation about tenure is that tenure is a two-way street: yes, the university makes a commitment to tenured professors, but tenure also enables professors to make a long-term commitment to the university and to the state. This dynamic came through clearly in my recent conversation with Professor Dana Fritz, Hixson-Lied Professor of Art (Photography) in the Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts. Throughout her time at UNL, tenure has enabled Professor Fritz to overhaul the curriculum in photography to ensure students’ visual literacy, engage in important service work to the institution, and, perhaps most importantly, produce a book about what was once the world’s largest hand-planted forest near Halsey, Nebraska, right before a fire destroyed a quarter of the forest and the nearby 4-H camp. Below is a summary of our conversation, edited for length and focus.

Niehaus: Tell me about your work in landscape photography.

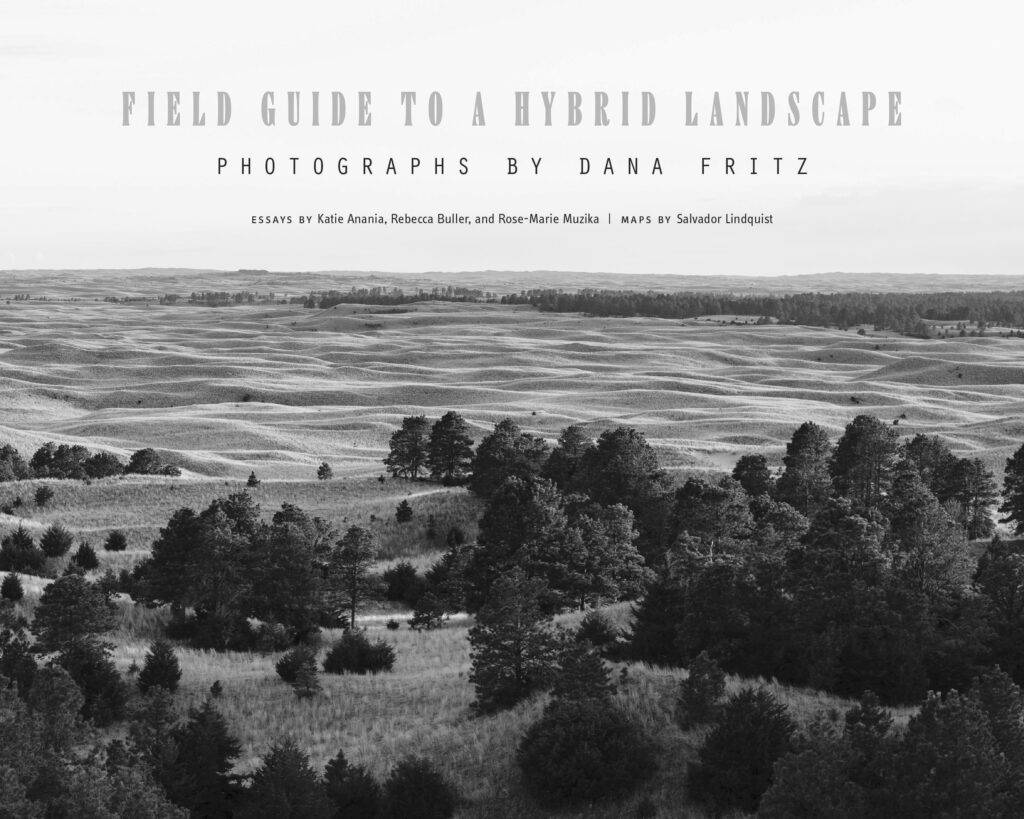

Fritz: My work focuses on understanding how we have shaped our ideas about wilderness, about conservation, about land value – our overall relationship to the land and environment. Last year I published a book called Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, which came out of my curiosity about why somebody would want to plant a forest in the middle of the sandhills. Ultimately the reason was Charles Bessey, a professor at the University of Nebraska and the father of modern botany. He came from Ohio, where there was widespread deforestation. Forests were being cut down for industrialization and railroads as settlers moved west. He was afraid there would literally not be enough trees for us to live in this country if we didn’t plant more trees. To address this problem, Bessey decided to start a timber industry in the sandhills of Nebraska. It never took off as a timber industry, but it ended up as the largest hand-planted forest in the world.

In the book I tell the story of the forces that shaped the landscape through photography. If somebody sees my book or my exhibition, they might relate to the pictures because they love the sandhills. They might relate to the pictures because they went to the 4-H camp and love the forest at Halsey. They might just like black and white landscape pictures. Maybe people find beauty in it, maybe people connect to it with their own memories or their own ideas. Or maybe they look at the pictures and think, wow, I never knew there was anything like this in Nebraska! We are kind of unknown to so many people.

Those are the visual ways in, but then I think if somebody reads the text, they will start to understand the story I’m trying to tell, which is a complex story of our environmental history and our own land relations, how we manage and treat the land. Ultimately, I hope my work helps people think harder and make more informed decisions.

The interesting thing is, I thought that the book was a contemporary interpretation of the forest, but sadly there was a massive fire that destroyed the 4-H camp and much of the forest in 2022. But I made all of those pictures before the fire – and the forest has changed forever. So my book is now a historical record of the forest. That is the kind of thing that can’t happen if I am here as a visiting professor without tenure.

Niehaus: Tell me more about that – how has tenure been important in shaping your work?

Fritz: Once I had tenure I could see myself doing different, bigger, more integrated, more consequential things, because I am not going to have to apply for another job and envision myself in another city. I would say that a book project like this takes a minimum of five years to work on, so if I am going to do that, I need to know where I am going to live. I can’t do this type of work as a roving visiting faculty member, or if I might need to move next year. The thing is, there is no other job like my job in Lincoln. The closest is my colleague’s job, but he and I have different specialties; we are not actually interchangeable. If I don’t have a job at UNL, I don’t have a job in Lincoln. I can’t do a five-year project about the sandhills if I suddenly have to live in Michigan or Florida.

Tenure really opens the possibility for long term investment in research and creative activity, in teaching, and in service. You still have to report what you do every year, but with tenure you don’t have to finish something every year. So much of what we do is bigger than a year.

Once I had tenure, I started thinking differently about myself at the university. When you have tenure, you commit to a place; you have a long view that just isn’t possible when you basically have to re-apply for your job every year. When we get tenure, we stay here. We not only commit ourselves to the university, we commit ourselves to the community, to the city. Tenure prevents brain drain; tenure keeps us here, investing, building, paying taxes. It is a mutual commitment between a professor and a university. This place has invested in me and I am going to invest in the place.

Niehaus: So how have you seen that mutual commitment play out in your work?

Fritz: Well, one important thing is that after I had tenure, I made a lateral move and assumed direction of the photography area when a colleague unexpectedly retired. I started a new graduate program and completely overhauled the curriculum. The reason I could do all of that is because of tenure, because I had been around the block, I understood the curriculum change process, and I understood how to get things done here. When I had to jumpstart something out of thin air, quickly, I could do it.

And really, if I hadn’t been able to do that, photography would have become just a service area with an adjunct teaching an occasional class. And that would be crazy! In this 21st century image culture, understanding images is one of the most important things we can teach our students, and we can’t do that without photography. Think about how we use our phones. Think about how we use images – images are everywhere. We are constantly bombarded with them. I can’t even keep up with the number of images that are made every second. And if we are ignorant of how to read and understand those images, we are sunk. We can’t ignore images in the same way we can’t ignore text. It is critical that we understand the image culture that we live in.

I am teaching students how to make images, too, how to take control over the images they are creating and how to understand what they are communicating with their images. I am teaching students how to take responsibility for what they want to communicate, because it is a responsibility when we put images out there. A lot of people do not take responsibility for the images they put on social media, using their phones. But I am trying to teach students to be responsible and to be ethical and to really think about what putting those images out in the world means.

Before tenure, I had my nose to the ground the whole time, just trying to get my work done, trying to make sure my classes were taught well, and spending a ton of time each year preparing a huge file of materials for evaluation. At any time they could say, yeah, this isn’t working. That was incredibly stressful.

Tenure helped me suddenly see myself as someone who would be around, who could contribute differently. Once you have tenure you are still evaluated, but there’s a different feel to it. Instead of spending all this time preparing a huge packet for evaluation each year and stressing about whether I have a job or not, I can spend my time thinking about what am I going to do now that I’m here? Really here?